7th March 2015 (weekly review)

A very slow week. Only one new species was found. Frustratingly, I managed to find the empty shells on no less than four species that I need to see. I am not yet desperate enough to start counting empty shells but if I get desperate towards the end of the year I might start giving myself half-marks for them.

My one new species this week – species number 21 – was:

Aegopinella pura, the Clear Glass Snail

There are two Aegopinella species in the UK, the other being Aegopinella nitidula. A. nitidula is a very common species, but is easily mixed-up with one of the Oxychilus species. A. pura, on the other hand, is reasonably distinct but less common in my experience. It is a reasonably small snail – max width of just over 4mm – and has a very pleasant ivory/pearl coloured shell. Picture by me:

Whilst I’ve found A. nitidula in gardens and waste ground, I’ve only ever found A. pura in leaf litter or in the bases of very mature hedges. At the Pulpit Hill and Grangelands Nature Reserve, which I visited this week with @RyanClarkNature & @BrianE_Cambs, we found A. pura in quantities far exceedingly the numbers I have seen at any other site ever. Presumably the underlying chalk and deep beech-leaf litter is particularly to their liking.

A good picture by @BrianE_Cambs:

The most distinctive feature of A. pura is the structure of the shell, though you’ll need a x20 lens in order to see it. The shell is marked with radial striations (similarly, but not as strongly as in Nesovitrea hammonis) as well as spiral striations. This means that shell, when viewed closely, has a pattern of what appears to be tiny squares. A picture of this by @BrianE_Cambs:

This week I plan to explore some riverside habitats in the hope of finding species such as Succinea putris, Arianta arbustorum and Zonitoides nitidus. Wish me luck!

28th February 2015 (weekly review)

February has reached its close and I have attained a grand total of 20 snail species on my quest. That’s ten species per month, so far, so keeping up that rate should see me achieve my overall target by the end of the year. Of course, the species I’m finding at the moment are relatively easy species to find and it will only get more difficult as the year progresses. My two new species this week were:

Clausilia bidentata, the Two-toothed Door Snail

This is my second clausilid species of the year, after Cochlodina laminata, and it’s probably the most widespread British species of door snail. Whilst Cochlodina laminata climbs trees occasionally in wet weather, Clausilia bidentata is often found on trees or walls. It grows to a maximum of 12mm tall and the shell generally looks quite ‘rough’ due to the density of ribbing. It also usually is marked with flecks of white.

The specific name – bidentata – clearly means the same as the common name; two-toothed, but I am not actually sure as to why it has been called this. There are two lamellae in the mouth of the shell – which could be referred to as teeth – but this is true of most of the UK clausilids.

The below picture shows an adult Clausilia bidentata (bottom) next to a sub-adult Cochlodina laminata (top). Note the size difference and how rough C. bidentata looks in comparison.

Nesovitrea hammonis, the Rayed Glass Snail

This is a very widespread species – recorded pretty much everywhere according to NBN – but is possibly over looked due to its small size (a smidge over 4mm fully grown) and the fact that its shell only ever grows to have 3 ½ whorls, which gives it a ‘juvenile’ appearance. It does, however, have one very distinctive feature: its shell is strongly marked with radial striations which can be easily seen at low magnification. This gives it the common name of the Rayed Glass Snail.

A better picture by @BrianE_Cambs:

This snail is one of the elite few that are tolerant of soil acidity and indeed the specimen that I photographed was found at The Lodge RSPB on the edge of the heath.

Hopefully I can find at least another ten species in March to keep myself on target. I’m hoping for some warmer weather to bring a few more species out of hibernation.

21st February 2015 (weekly review)

It’s been a pretty quiet week with only two new species. There are a few species that I would classify as being common or easy to find locally (Candidula intersecta, Cernuella virgata, Helicella itala) that I am just not encountering – I’m guessing that these species are still hibernating. I can’t find any information on where these species spend the winter but I’d guess they spend it underground, hence why I can’t find them. Hopefully in a month or so these will start cropping up so that I can tick them off my list.

In a break from the norm I’m going to describe this weeks’ species together due to their close similarity.

Carychium minimum and Carychium tridentatum, Herald Snail and Slender Herald Snail

These species are very widespread in woodland leaf-litter and they stand out amongst leaves and on the underside of logs due to being a beautiful ivory-white colour. They are very easily overlooked, despite their colour, due to being a maximum of 2mm tall and usually a little smaller.

However, once found, they are very easily recognised as being one of the ‘Herald Snails’; a Carychium species. The trouble then lies in separating the two species in the genus. As the name suggests, the Slender Herald Snail, C. tridentatum, is proportionally narrower than the Herald Snail, C. minimum. This, as I will testify, is a tricky feature to judge without both species present or some comparative material.

Here is a wonderful picture by @BrianE_Cambs that shows the Slender Herald Snail on the left and the Herald Snail on the right. The difference in shape is quite obvious

Unfortunately, as I hinted above, when one species is found singularly they are a lot harder to differentiate. The following pictures are of one of the Carychium species, but I’m not sure which one.

In this picture by @MarkGurn it is possible to make out the snail’s eyes. In this species, unlike many larger snails, the eyes are at the base of the tentacles and look like black dots.

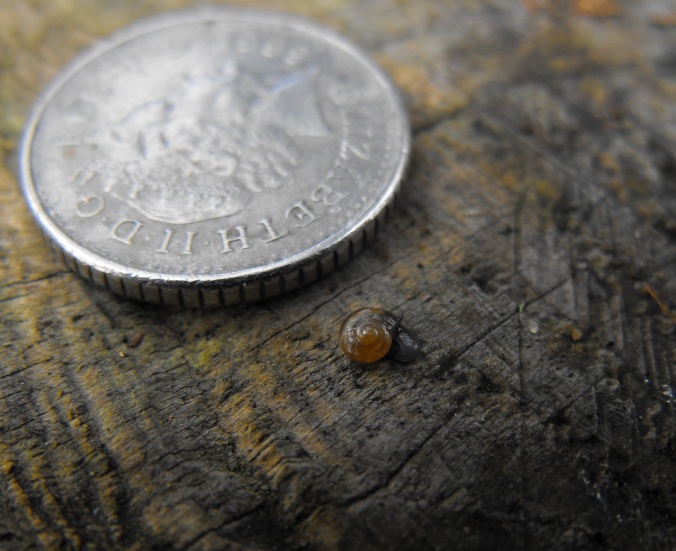

Tiny snail being adorable by @ASpeciesADay

Also, for a sense of scale.

Great picture by @MarkGurn of a scatter of shells in the palm of my hand. Live shells are translucent, empty shells are opaque.

Fantastic picture by @ASpeciesADay of shells on a five pence – tiny snails!

Both species can be found in woodlands, particularly in ancient woodlands, amongst deep, stable leaf-litter. C. minimum, however, can also be found in wetland habitats. They usually only tend to overlap in slightly damp, ancient woods.

Oh, and in case you were wondering why these two species are separated out at all and are not just treated as two ends on a spectrum of variation, these two species can also be separated on distinctive internal anatomy of the shells.

I’m up to 18 species now overall. Ideally I’d like to have seen a few more species than that, but I’m sure as the weather starts to warm some species will be a lot easier to find.

14th February 2015 (weekly review)

I hadn’t realised until now, but it’s Valentine’s Day. Interestingly, snails possibly have a modicum of credit for some of the imagery that people are exposed to on this day. Cupid’s bow with its arrows that cause infatuation might be based on the ‘love-darts’ that many species of larger snail jab into each other during copulation. As the Wikipedia article states:

‘Some writers have commented on the parallel between the love darts of snails and the love darts fired by the mythological being Cupid, known as Eros in Greek mythology.[7] It is even possible that there is a connection between the behavior of the snails and the myth. Malacologist (mollusk expert) Ronald Chase of McGill University said about the garden snail Helix aspersa, “I believe the myth of Cupid and his arrows has its basis in this snail species, which is native to Greece”. He added, “The Greeks probably knew about this behavior because they were pretty good naturalists and observers.”

In some languages, the dart that these snails use before mating is known as an “arrow”. For example, in the German language it is called a Liebespfeil or “love arrow”, and in the Czech language it is šíp lásky (which means “arrow of love”).’

For some footage of copulating snails, complete with love dart, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ddo_6GqmweY

This week I have seen two more species for my quest, bringing me up to 16 species. I have, however, added two new species to my list this week which means I still have a round 100 species to track down and see. My new snails were:

Cepaea hortensis, the White-lipped Snail

I actually found a few of these in quick succession. A few were found at Potton Wood amongst leaf litter, and more examples were found at Sharpenhoe Clappers on the edge of the Chilterns. Cepaea hortensis reaches a maximum width of about 22mm, smaller at full size than Cepaea nemoralis which can reach 25mm. It is a very common species, more tolerant of colder conditions than C. nemoralis and as such its range extends further into Scotland than that species. The specific – hortensis – means ‘of the garden’ and aptly describes a portion of the habitat it can be found in.

As I mentioned when I wrote about C. nemoralis, these two species can usually be distinguished by the colour of the lip of the shell. In C. nemoralis, the ‘Brown-lipped Snail’, the lip is usually brown. In C. hortensis, the ‘White-lipped Snail’, the lip is usually white. This, whilst a decent general guide, isn’t 100% accurate. The photo below shows two C. hortensis on the left – one of which possesses a brown lip – and a typical brown-lipped C. nemoralis on the right.

Assiminea grayana, the Dun Sentinel

I didn’t originally have this species on my target list as it doesn’t occur in Robert Cameron’s guide or on the pictorial key. However, @ABugBlog insisted I include it and so, whilst visiting my parents yesterday, I walked down to Brough Haven and the edge of the Humber estuary and soon found large numbers amongst the reeds on the shore.

The reason, I assume, that it doesn’t occur in either of my guides is that it is treated as a marine snail that happens to live in semi-terrestrial environments such as reedy or saltmarsh areas. As such, it is found along much of the coast of the British Isles and quite far inland along estuaries.

It grows to a maximum of 6mm tall and lives at or just above the high tide mark. It is usually very abundant where it occurs; often under driftwood, stones and other assorted detritus. I found a lot yesterday under a discarded plastic water butt.

I have no idea where the common name ‘Dun Sentinel’ comes from, but I really like it. Dun, presumably, refers to the colour of the shells, but I’m not sure why ‘Sentinel’ was chosen.

So there’s my week; another two species for my list, 16 seen overall with another 100 species left to go.

Subsequent snails (more molluscs?)

It has very recently come to my attention that there is another species of land snail that I need to add to my quest, so I am now aiming to see the grand total of 115 species during 2015. I already had eleven hothouse alien species on my list, but now, I have been informed, there is a twelfth: Allopeas gracile.

As of yet, I’m not even sure where this species has been recorded from. That’s not particularly surprising as I have yet to get solid information on a few of the greenhouse exotics. In fact, here is my current hothouse list below and the sites in which I think they occur:

Zonitoides arboreus – I’ve heard that this species has been found in the Cambridge Botanic Gardens as well as a garden centre in Oxfordshire. Possibly in Kew Gardens?

Helicodiscus parallelus – From looking on NBN, it looks as though this has been found in the Cambridge Botanic Gardens. That’s the only dot on the map and the only bit of information I have. If any readers have any more details, please let me know!

Pleurodiscus balmei – Apparently found in Glasgow Botanic Gardens. Additionally, seems to show a dot on Kew Gardens. Any more information would be much appreciated.

Gulella io – Kew Gardens and the Cambridge Botanic Gardens.

Hawaiia minuscula – There is a dot on NBN for Cambridge Botanic Gardens, and one that appears to be in Nottingham. That’s all I know.

Kaliella barrackporensis – This species doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page to link to, and I can’t find it on NBN. My beautiful ‘Illustrated Guide’, however, says ‘We also include… Kaliella barrackporensis, which was recently found living in the Tropical Biome of the Eden Project in Cornwall’.

Rumina decollata – Apparently found, or was found, in Caerphilly Garden Centre, South Wales. There is also a dot on NBN for Kew Gardens.

Subulina striatella – Apparently has been found at Kew and the Glasgow Botanic Gardens. Mark Telfer has mentioned the Eden Project as another site

Subulina octona – Cambridge Botanic Gardens, Kew Gardens and the Eden Project.

Opeas hannense – NBN has a dot for Kew and there are scattered dots elsewhere.

Allopeas clavulinum – There are no dots on NBN and I can’t find any references to where it occurs in the UK. All I have to go on is my illustrated guide which has a picture of it, thus tacitly stating that it can indeed be found.

Allopeas gracile – Doesn’t appear on NBN, but I have found a reference to it being recorded at the Cambridge Botanic Gardens in 2011.

If readers know more about any of these species then please either comment below or contact me on Twitter @UKSnailTrail

7th February 2015 (weekly review)

It’s been a snowy, icy, wet, muddy week and these are not ideal conditions for seeking snails. Or even to encourage me to find snails.

Nevertheless, despite the less-than-desirable weather, I struck out on my quest and found two new species for my total, bringing me up to 14 species. A passable amount so early in the year, I hope. My new species were:

Trucatellina cylindrica, The Cylindrical Whorl Snail

My first species of the week was Trucatellina cylindrica, a species I was so excited about that I wrote a blog post specifically devoted to it. I’ll try not to repeat myself too much.

With a maximum width of 0.9 mm and maximum height of 2mm, this is the smallest snail I have found so far this year. It is also the rarest, with it only being known to survive at three sites in Britain. It was formerly much more widespread, with archaeological records from Cambridgeshire, Northumberland, Kent, Herefordshire and Northamptonshire being easily found on a quick google search.

Clearly, this species was once more widespread, but how does a species this small ever distribute itself anyway? Does it rely on unbroken habitats and thousands of years to spread? Perhaps not. This paper makes the claim that small snails – including Truncatellina species – could be distributed between neighbouring islands by wind.

Cochlodina laminata, The Plaited Door Snail

The door snails are one of my favourite groups – possibly because they deviate so much from the ‘typical’ form that most people associate snails with. The door snails get their name from the fact that they have an internal structure that they can move to close the mouth of the shell – like a door. This is presumably used to deter the attention of predators, but I wonder if it also serves a purpose in retaining moisture during periods of dryness. This internal structure is called a ‘clausilium’ and from this comes the name for the door snail family: Clausiliidae, of which there are eight species in the UK. Cochlodina laminata is probably the second most common species in Britain – but relatively uncommon and localised in Ireland – and can be found amongst leaf litter and around fallen logs; it occasionally climbs up trees in damp weather. It can grow to a hearty 17mm long.

Juvenile shells are very glossy and translucent and can look like a different species to a fully mature individual, which are opaque and often have worn or bleached areas to the shell.

Note: The clausilium is not to be confused with an operculum which, whilst possibly serving the same sorts of purposes, is a completely separately evolved feature. Only two terrestrial snails in the UK possess opercula – Pomatias elegans and Acicula fusca.

I’ll be travelling a bit next week. This could either make snail-hunting difficult, or expose me to different species in a different area. We’ll see!

The finding of Truncatellina cylindrica

Truncatellina cylindrica is one of the less-common and more-awkward species of snail to find in the UK. As far as is known, it survives at three sites in the UK; one in Yorkshire, one in Bedfordshire, and one in Norfolk – though it is quite possible that undiscovered or overlooked colonies might exist elsewhere. Additionally, the snail is very little. Extremely wee. Positively minute. It grows to an absolute maximum of 2mm tall, but is usually smaller, with a maximum width of 0.9mm.

Luckily, the Bedfordshire site for this species is approximately a five minute walk from my house, though ‘site’ is a rather strong word. The snail only seems to occur on the verge between the church boundary wall and the road and, in fact, seems to be restricted to within 30cm of the base of the wall.

The church and the wall.

Another view. That’s pretty much it.

And for good reason

I found a document describing a survey for Truncatellina cylindrica sites in Bedfordshire, and this gave me some idea of how to search for the species.

I collected a specimen tube worth of soil from the very base of the wall. I was wary of damaging the site and so only took the single sample, comprising about 5ml of material. I took this home and tipped it onto a white plate. Then, using a cocktail stick, I carefully, bit by bit, moved particles of soil from one side of the plate to the other. A success came quite early on as I soon discovered an old, empty shell of my target species. I carefully transferred it to a specimen tube. Then followed a long period of a calm before I found two living juvenile shells within minutes of each other. The first was fresh but empty, but the second held a living individual. Success! The rest of my sample yielded only another old broken shell, but I was delighted by my success – four shells, two living, from 5ml of soil.

Unfortunately, the snails were too small for me to capture with any clarity using my camera, so I was forced to beg around at work for assistance. Luckily a colleague, @aspeciesaday, obliged and took these marvellous photos:

31st January 2015 (weekly review)

I’ve spent a fair proportion of this week considering the year ahead. So far I have been mainly searching for snails in my immediate local area and I imagine that I can probably double my current total by continuing to do this. Of course, there are many species that don’t occur within walking distance of my house, or even within my current county of residence. Thus I have been searching NBN and canvassing my Twitter followers to help sort locations for some slightly more obscure species.

After doing this I came to a conclusion; the Vertigo snails are going to be really difficult. I mean, I knew they were going to be difficult before I started – that was the group that I was most unsure about – but everything I read just makes them seem even more obscure. Thankfully, I’ve already had sites recommended to me on Twitter that might hold three Vertigo species. If these work out that only leaves me with eight more Vertigo species to see…

This week I saw a grand total of two new species, bringing my overall total up to twelve.

My new species are:

Vallonia excentrica, the Eccentric Vallonia

This is my second Vallonia species of the year, coming after last week’s Vallonia costata. I’ve only got one species in this genus left to go now, Vallonia pulchella.

I found these in an abandoned quarry near Potton, Bedfordshire. Clearly, they must have spread into the site since the quarry was abandoned. Unfortunately I don’t know how long ago the quarry ceased operations, otherwise that could give a rough idea of the power of dispersal that these snails have.

There is a fair amount of detritus scattered around in the quarry – bits of wood, stone, plastic etc., – and these serve as excellent places to try and find Vallonia. However, in my experience, Vallonia only seem to be found under refugia that have been relatively recently moved. Bits of stone or wood that have been there too long kill off the grass underneath and I never find Vallonia in these circumstances. Recently moved refugia, which have been in place just long enough to make the grass go slightly yellowish and sad-looking, seem to be the best places to search. Usually the shining, ivory shell of Vallonia is not too difficult to spot in these situations.

Vallonia excentrica can be easily differentiated from V. costata by the lack of heavy ribbing on the shell, as well by the way that the outermost whorl of the shell expands rapidly, giving it an ‘eccentric’ or ‘unbalanced’ appearance. This, obviously, gives it both its common and scientific names. Distinguishing between V. excentrica and V. pulchella is more subtle, and will be discussed if-and-when I find that species.

Cepaea nemoralis, the Brown-lipped Snail

I can’t believe how long it took me to find this species, especially with how large, common and colourful it is. All I seemed to be able to find were empty shells. Amusingly, after spending some time searching for this species, I found this one half-heartedly and absent-mindedly whilst aimlessly turning over logs whilst chatting to my Mum on my phone during my lunch break.

There are two Cepaea species in the UK; C. nemoralis and C. hortensis. Cepaea nemoralis is the larger of the two species – growing up to a max of 25mm in width – and usually has a brown lip to the mouth of the shell in mature specimens, hence the common name. Cepaea hortensis, by contrast, usually has a white-lip to the shell. Of course, rules are made to be broken, and in some areas of the UK Cepaea nemoralis occurs in populations that contain forms with a white-lip. In these cases it is probably best to:

- Look at the maximum sizes of shells ( nemoralis is larger than C. hortensis)

- Ask an expert to dissect for confirmation

- Give in and look elsewhere for more cooperative snails.

The scientific name comes from the Greek ‘cepaea’ meaning ‘of the garden’ and the Latin ‘nemoralis’ meaning ‘of the woods’. This is a fair descriptor of habitat, as the species tends to favour habitats disturbed by humans, such as gardens, parks, arable land and roadsides.

Cepaea nemoralis is almost obscenely polymorphic, occurring in a staggering array of colours and patterns, even within a single population. This collection of drawings and this photograph do a marvellous job of demonstrating variation. They also exhibit rapid, habitat related evolution when colonising areas from which they were previously absent – thanks to @schilthuizen for the article.

I also found a heap of dead shells during the week. It appeared to be an area in which empty shells naturally accrued rather than a thrush’s anvil, as most shells were completely intact. I called this a ‘snail-graveyard’ but Twitter follower @fionagilsenan suggested the substantially better name of ‘snail-midden’.

I arranged the snails by species. From right to left; Cepaea species, Monacha cantiana, Cornu aspersum and…. Helix pomatia!

I’ll have to came back later in the year to try and see a live and intact one of these – they are the largest UK land snail and are all-round gorgeous beasts.

Once again, if you’re not following me on Twitter please consider doing so at @UKSnailTrail.

For further, more in-depth information on snails and other molluscs, please check out the website of the Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

24th January 2015 (weekly review)

This week I joined the Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland and I encourage anyone with an interest in snail identification, snail recording or snail conservation to join. Honestly, please consider it. I haven’t regretted a single moment of my three days of membership so far.

I have been a bit slower in terms of snail finds. I think this is down to a combination of more wintry weather conditions – there’s been frost almost every day this week – and the fact that I might have found many of the commoner species in the local areas in which I’ve been searching.

Still, I managed to find three new snails, bringing my yearly total up to ten species. My three new species are:

Hygromia cinctella, the Girdled Snail

This species was kindly shown to me by Africa Gomez of @abugblog in the Pearson Park Wildlife Garden in Hull. This snail has a distinctively patterned and shaped snail. It has the form of a very shallow cone, with a rounded base, and is marked with a white line that encircles, or ‘girdles’, the shell. This white line follows a sharp ridge or ‘keel’ that runs around the shell and, combined, these features make it an easy species to distinguish. Maximum width of shell is 12mm.

The Girdled Snail is a non-native species; first described in Britain in 1950 by writer Alexander Comfort. There are, however, records of this species that extend back to 1945 but were misidentified at the time as being Hygromia limbata. The species remained fairly restricted to the south-west until the 1970’s, at which point it began to expand dramatically, being recorded in Scotland for the first time in 2008. The Girdled Snail is native to the Mediterranean region and it surprises me how well it seems to cope – and thrive – in the UK.

Africa pointed out to me that the Wikipedia article on Girdled Snail was a ‘stub’; an incomplete article with less than 500 words. Working together, we updated and improved the text on the page, and Africa added some of her own photos. View our success here!

Discus rotundatus, the Rounded Snail, Rotund Snail, or Discus Snail

Discus rotundatus is one of my favourite UK snails. I remember the first time I saw it being struck by its wonderful mottling in shades of brown, pink and cream, as well as that densely ribbed shell. It grows up to about 7mm in maximum diameter and is commonly found in moist, shaded places such as parks and graveyards, as well as in more natural habitats such as woodland.

Cornu aspersum, the Common or Garden Snail

This is one of those species that’s possible just to ramble on about endlessly. Firstly, this is the beast that quite possibly gave rise to the phrase ‘common or garden’. It’s not often you meet an invertebrate with its own idiom! It’s also the largest of the common snail species – about 40mm in width – with only two other less-common UK species, Helix pomatia and H. lucorum, being larger.

Cornu aspersum was, for many years, called Helix aspersa. It was then decided that it didn’t belong in the genus ‘Helix’ and was moved to ‘Cornu’. However, whilst ‘Cornu’ was the name given to material identifiable as this species, the original specimen was an aberrant scalariform individual (a snail in which the whorls of the shell grow apart from each other). This, according to some schools of thought, means that the genus name is invalid. A summary of this problem can be read here.

Numerous hibernating individuals can often be found over winter, gathered together under logs or in cracks in trees or rocks. If a hibernating snail is dislodged it should be possible to see the congealed film or plug of mucus that seals the moth of the shell; this is called an epiphragm.

Cornu aspersum is another non-native snail, but this one is an ancient, possibly Neolithic introduction. It is common in parks and gardens as well as other areas modified by people.

Once again, if you’re not following me on Twitter please consider doing so at @UKSnailTrail.